Above: Oscar Singer and his wife Eva

Above: Oscar Singer and his wife Eva

Written By: Heidi Singer

Photos By: John Packman

Dr. Oscar Singer’s mind is a mystery. Most days the former physician sits in his wheelchair surrounded by colourful canvasses he once painted and books in several languages he once read, quietly watching sports on TV.

He can still feed himself, but he has trouble swallowing. On a good day, the 88-year old Holocaust survivor can read a newspaper and even say a few words in German, Hungarian or English. But nobody knows whether he understands the words. Does he have Alzheimer’s? Dementia? Parkinson’s? Even his diagnosis is unclear.

“If I think about it,” says his wife, Eva, 83, sitting in the beautiful, antique-filled living room of their North York home, “I cry sometimes because he had a fantastic mind, and to see that going is very sad. He’s very sweet, a wonderful person.”

Oscar takes medications, but Eva doesn’t think they’ve done much good. That’s not a surprise. About a hundred drugs have been tested for Alzheimer’s and dementia and the vast majority have failed outright. A few improve symptoms for a while.

Dr. Graham Collingridge knows those statistics well. A world authority on the connection between memory and brain plasticity — the process by which the mind reinvents itself — Dr. Collingridge participated in the research underpinning the commonly prescribed Alzheimer’s drug Memantine. Now, the British-born physiologist is building on the partial success of that drug — doctors tell him it can stave off memory loss for up to a year — to develop the science that he hopes will lead to a far more powerful version of it.

“We have to fully grasp the way memories are formed before we can understand why they’re lost,” says Dr. Collingridge, Senior Investigator at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute (LTRI), part of Sinai Health System. “I believe the key is in the power of plasticity. If the brain’s wiring is capable of change, then we’re capable of changing the destiny of neurodegenerative disease.”

Above: Eva and Oscar Singer in London on their wedding day, September 12, 1959

Above: Eva and Oscar Singer in London on their wedding day, September 12, 1959

The mystery of Oscar Singer’s mind is mirrored, frustratingly, by the increasingly complex puzzle of neurodegeneration itself. In the genomic era, with whole-genome sequencing, scientists are starting to understand just how individual a person’s disease can be. They’re now questioning whether Alzheimer’s is one disease or dozens, or even thousands. The more researchers peer into the brains of the afflicted, the more genetic mutations they identify — DNA errors that could be a smoking gun in one person’s disease and a red herring in another’s. And the lines between diseases like dementia and Parkinson’s are blurring. There appears to be substantial overlap in the pathways used by the different illnesses of the mind, including psychiatric conditions and even ordinary depression.

To date, most researchers and drug companies have focused on the so-called “plaques and tangles” that typically appear in scans of Alzheimer’s brains. But nobody knows whether they’re a cause, a symptom or both. The latest hope for a treatment crashed last year, when a much-anticipated drug broke up the plaques but failed to significantly improve the symptoms of disease.

All of this may sound hopelessly discouraging, but to Dr. Collingridge, these are exciting days for research into brain disease. Scientists are finally starting to understand the physiology behind these conditions, and he believes stepping back to basics will result in a very big step forward.

“It’s an optimistic time because we’re getting closer to understanding the underlying pathology” of brain disease, says Dr. Collingridge, who is also Chair of the Department of Physiology at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Medicine.

The first of these breakthroughs occurred with the development of a theory that memories are formed at the connections between nerve cells, called synapses. (“Cells that fire together, wire together,” is the shorthand explanation.) When the communication between two neurons is going well and there are no glitches, the connection between them gets stronger, allowing memories to be stored. Then it was discovered how synapses can get stronger or weaker in response to their activity. This process, says Dr. Collingridge, is now widely regarded as the best explanation for how memory works.

The first breakthrough came from the Canadian psychologist, Donald Hebb, and the second by fellow Brit Tim Bliss, who was a graduate student at McGill University. So perhaps it was fitting that Dr. Collingridge developed the third while he was a young researcher at the University of British Columbia in the 1980s.

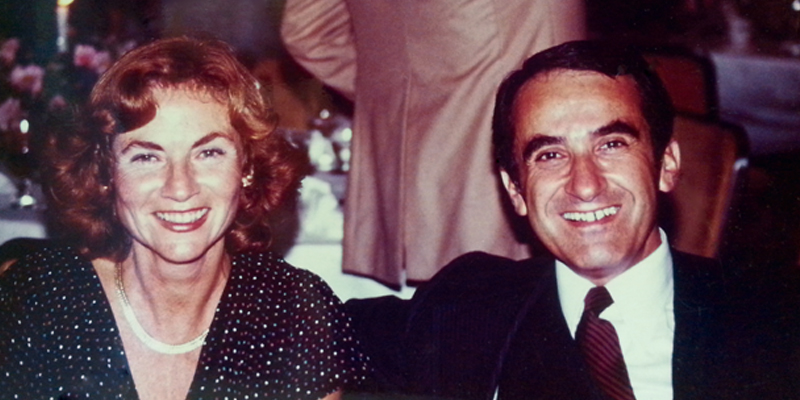

Above: Eva and Oscar in Montreal attending the wedding of their niece in 1979

Above: Eva and Oscar in Montreal attending the wedding of their niece in 1979

Dr. Collingridge discovered the mechanism that makes the synapses get stronger or weaker: a tiny part of the nerve cell called the NMDA receptor. He used a drug that blocked the receptor, and showed that this stopped the synapses from getting stronger. A third neuroscientist, Richard Morris, then demonstrated that the same drug blocked the formation of new memories. On the strength of that discovery, Dr. Collingridge, together with Drs. Bliss and Morris, last year was awarded the Brain Prize, the world’s top honour for neuroscience.

Dr. Collingridge assumed that blocking the NMDA receptor would be a bad thing: Wouldn’t you want brain signals to be firing strongly to create solid memories? This turned out to be true. But to his surprise, Dr. Collingridge found there could be too much of a good thing. Not only was too little NMDA receptor activity bad for memory and thinking, too much was also detrimental. The important thing was to normalize this receptor. The drug Memantine, now the frontline treatment for mid-to-late stage Alzheimer’s, emerged directly from this research and is the first to attack Alzheimer’s by working to regulate the NMDA receptor.

In his lab, Dr. Collingridge is building on this first-generation research to understand more about the process of plasticity, and how to achieve it through tuning up or down those synapses in the brain. The goal is to develop a more effective version of Memantine. Meanwhile, only half of the molecules involved in memory have been identified; Dr. Collingridge is trying to understand more about how they work, and to discover new ones that could be the next drug targets.

“I cry sometimes because he had a fantastic mind, and to see that going is very sad. He’s very sweet, a wonderful person.”

- Eva Singer

The LTRI is a “fantastic environment for research, both because of the outstanding basic science and particularly having world-leading experts in the sorts of molecules that I’m interested in,” he says. “Also, being embedded in a hospital connects our lab with patients in a way that we never had in the UK.”

His own theory about the cause of Alzheimer’s revolves less around the buildup of toxic plaques and centres on those nerve connectors, the synapses. In the healthy brain, we are able to prune away old, unused synaptic connections, like a gardener might do with dying roses. But in Alzheimer’s, something goes badly wrong in this process so that important connections — beautiful, live roses essential to the garden’s beauty — are pruned away too. “You start chopping away at connections you don’t want to lose,” he says.

Eva Singer has never met Graham Collingridge, but every day she gives her husband the drug he helped develop. As a scientist herself (a chemical engineer in her native Hungary), she keeps an eye on Alzheimer’s research. Eva doesn’t believe that a blockbuster drug will emerge in time to help her husband, but she is confident that she can manage him at home with all-day help from aides provided by Sinai Health System’s home care partner Circle of Care, along with other agencies and her son. She is so confident that she passed up opportunities to place Oscar in top facilities, and recently, she took his name off their waiting lists.

“Some Alzheimer’s and dementia patients can become aggressive, and their personality changes,” she says. “I must say that I’m lucky in a way that he is very easy and very sweet. I decided as long as I’m able to do it… I’m going to keep him at home. It’s better for him and he’s happy. He does recognize me — he calls me by name. I’m a steady point in his life so I would not change this at all.”

Eva recalls when Oscar’s memory problems worsened five years ago, during a trip to Europe. After they returned, she gently suggested it was time to give up his position working one day a week with a North York physician. Oscar was 83, and had once been Chief of Paediatrics at Scarborough Centenary Hospital (now Rouge Valley Health System). It was a sad day: First he was going to lose his lifelong identity as a doctor. Next, would he lose his identity as a man, a father and husband?

Eva recalls when Oscar’s memory problems worsened five years ago, during a trip to Europe. After they returned, she gently suggested it was time to give up his position working one day a week with a North York physician. Oscar was 83, and had once been Chief of Paediatrics at Scarborough Centenary Hospital (now Rouge Valley Health System). It was a sad day: First he was going to lose his lifelong identity as a doctor. Next, would he lose his identity as a man, a father and husband?

But even today, he’s still Oscar to his wife. He still says a few words and it’s still his voice and his smile and his sweet temperament. Not long ago, their eldest son, also a physician, visited from St. Louis. Oscar sat quietly, surrounded by his paintings of scenes from the past — houses he’s stayed in, the abstract paintings that are Eva’s favourites and a vibrant depiction of Piccadilly Circus from his time in England, after surviving the war and Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

“I said, ‘Just sit next to him. Hold his hand, and I know that he recognizes you. He can’t talk to you. You can’t talk to him and ask how are you, Dad? But just hold his hand. He’ll smile at you and he’ll know you’re there. He’s still your father.’”